Proportional representation and health

Proportional representation matters to our health

Population Health

Patterson (2017) studied the experience of 179 countries with different types of democratic or autocratic regimes between 1975 and 2012 and found that countries with proportional systems most reliably outperformed other countries with regard to population health. Compared to “closed autocracies” at the other end of the spectrum, countries with PR had up to 12 more years of life expectancy on average, 75% less infant mortality, and lower mortality rates for most other age groups. In contrast, countries with winner-take-all systems were not better than closed autocracies in terms of health improvements over time. The authors conclude that democracies are not equally effective at holding leaders accountable and that broad representation of diverse interests appears to be what matters most to ensure positive health outcomes.

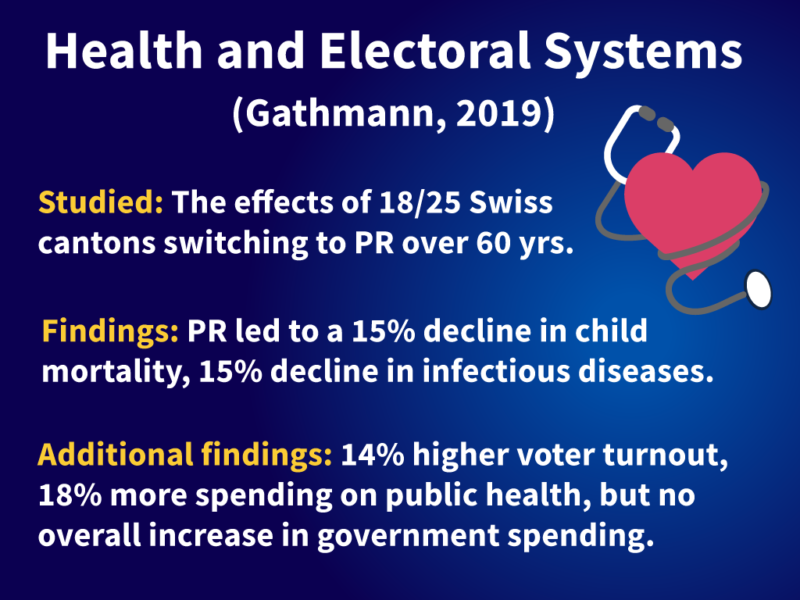

Effect of adopting proportional representation in Switzerland

Christina Gathmann (2019) exploits a unique time-series database from Switzerland, where, between 1890 and 1950, eighteen of the country’s twenty-five cantons switched to proportional representation in a staggered way. She was thus able to exploit a data set of multiple before and after scenarios against which to assess the impact of changing over from a plurality to a proportional system.

She documents a “sizable shift in political participation and representation when cantons switched from a majoritarian to a proportional system… (that) gave the previously underrepresented working class a greater weight in the political process.” This led to changes in public spending, most significantly in the education sector, with ultimate benefits in terms of population health. She estimates that the electoral reform contributed between 11 and 17 percent to the observed decline in mortality during this period.

This is a sizable contribution considering the role of other factors, including major advances in sanitation and medical practices during this period. As she points out, “such sizable mortality reductions demonstrate that electoral rules and hence, the form of democratic representation have powerful consequences for population well-being.”

Population Health

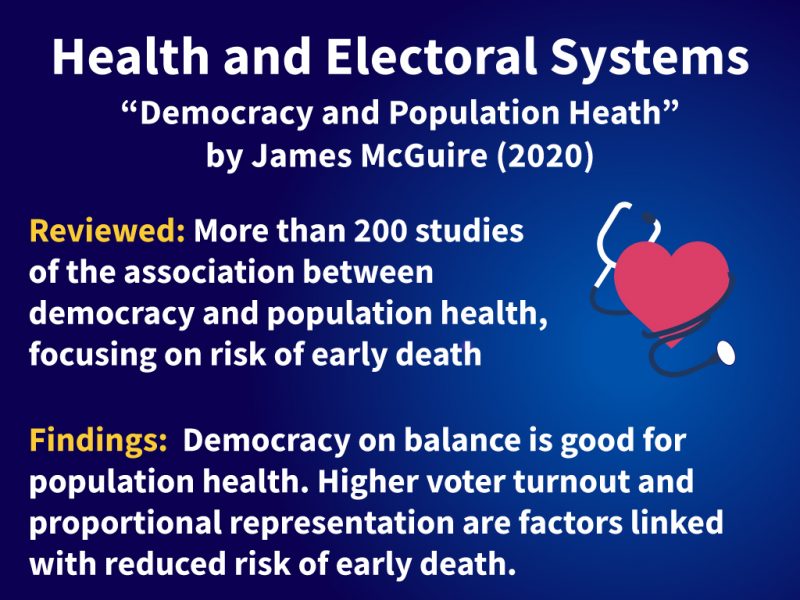

From the interview with author James McGuire, author of Democracy and Population Health (2020), Cambridge University Press.

“For my forthcoming book, Democracy and Population Health, I reviewed more than 200 quantitative studies of the association between the two phenomena. On balance, these studies find that democracy is usually, but not invariably, beneficial for population health.

Besides establishing that democracy on balance is good for population health, the studies I reviewed found that electoral contestation, although important as a determinant of population health, is not the only aspect of democracy that reduces the risk of early death. Long-term democratic experience appears to be important as well, as does decentralization, high voter turnout, proportional representation, and left-party strength.”